Free shipping on orders in the continental U.S. over $199. Shop Now

To celebrate the two year anniversary since the opening of April’s solo exhibition show at the Saginaw Art Museum, we decided to re-release this essay written about her career and artwork. If you didn’t know, Molten Sensuality: The Crystalline Creations of April Wagner was exhibited from October 5, 2018 – January 12, 2019. This marked April’s first solo museum exhibition. We hope you’ll enjoy this look back!

James Tottis, Adjunct Director of Collections and Curatorial Affairs at Saginaw Art Museum, did a wonderful job curating April’s first solo museum exhibition, Molten Sensuality : The Crystalline Creations of April Wagner. He put together this amazing essay as a companion to the exhibition. Whether or not you make it to the exhibit (we hope you do!), we wanted to share this piece with you to get a glimpse into April’s artistic career and how it is inspired by various parts of glassblowing history. Enjoy!

By: James W. Tottis

Edited by: Susan Higman Larson

Mesmerizing and enticing: glass has captivated humanity from the ancient Egyptians to twenty-first-century smart-phone devotees. April Wagner (b. 1973) has taken this ancient molten material and, with her very breath, become its master – forming vessels, orbs, disks, fans, and ribbons into sculpture for a tabletop or to cascade down the side of a building.

Glass is as likely to be found in a chemistry lab as in an art gallery. It can be clear, transparent, translucent, or opaque; it can be blown, molded, rolled, or spun, and produced in every color of the spectrum. A man-made creation that shimmers, reflects, and creates patterns with light and bends light into colors; glass is utilitarian as well as decorative. It can provide protection from the elements, and it can also scar the human body. It can be formed into a vessel to hold medicine, in one culture, and that bottle can be melted and repurposed as decorative elements for a different one.1 Created through various chemical cocktails—solutions, mixtures, or suspension—glass, in a molten state, hardens quickly once cooled. Yet between those states, it can be manipulated into shapes. When masterfully handled by an artist such as Wagner, the molten goo can be transformed into a hollow orb or a sensuous, sinuous elongated ribbon.

Left: Turchina Filigrana II, 2002, April Wagner

Collection of Kitty and Fred Lavery

There may be a certain irony to the fact that Wagner was born and spent her formative years in Muskegon, located on the silica-rich beaches of Lake Michigan. Silica is an essential ingredient for glass. “Muskegon has the most beautiful beaches in the world. Fine white sand, clear blue water. I have always loved being near water; I could never imagine myself in a place like Arizona.”2 Her artistic interests were first expressed during summers at her grandmother’s country house, where she would sit at the end of the driveway fashioning rudimentary sculptures and vessels out of its clay.3 These early creations led her to the Blue Lake Fine Arts camp, in Twin Lake, Michigan, initially for music and then to explore the fine arts. Later, at Muskegon High School, she enjoyed art and writing classes 4 before transferring to Interlochen Fine Arts Academy, also in Michigan, where she worked in ceramics and metalsmithing. After graduation, she enrolled at the New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University, in Alfred, New York, the leading ceramics program in the country. While there, she discovered printmaking, papermaking, and, most importantly, glassblowing.5

Art Students who are intensely driven often find access to studio time frustrating, and that was Wagner’s situation at Alfred. Thus, when glassmaking became her priority, she transferred in her junior year to the Center for Creative Studies (CCS), in Detroit: 6 “I came to Detroit to get the things I needed that I could not get at Alfred: space and time. I had a huge studio at CCS and access to the glass facility at any time of day or night. CCS’s glass program allowed me the freedom to create my own path; I was very self-motivated. Going to boarding school gave me a leg up, I’d say, on being self-reliant and accountable.”7

Wagner also had a deep desire to be in a city. During her senior year, she spent a semester at Urban Glass in Brooklyn on a Pratt-sponsored studio residency. She believed that spending time in New York would be important for her artistic growth, but discovered that the city did not have as strong a focus on contemporary glass and glass artists as other regions.8 Instead, she immersed herself in Detroit, which she found to be a wonderful backdrop and “…reminiscent of a town out of the old west; lawless, wild, free, and welcoming to adventure. There were so many opportunities to explore unfettered by oversight. I never had any negative experiences, which I know did happen, but I found the city welcoming in spite of or perhaps because of the epic decay and abandonment.”9

Wagner initially began signing pieces epiphany in 1993, which she defines as “insight into the essence of an object and/or material.”10 This moniker is now applied to her line of functional, semi-functional, and decorative objects. Over the next several years, her work tended more toward vessels and decorative objects, as she concentrated on refining her craft. At the same time, she began a search for an appropriate location for her studio. Unlike that of a painter, sculptor, or even a ceramist, the studio of a glassmaker has physical requirements that prevent it from being housed in a more traditional space. This is a centuries-old problem – one that the great glass center of Venice addressed in 1291. On fear that an accident at one of the glass furnaces would result in a devastating city-wide fire, the Venetian Republic ordered the destruction of all foundries within the city, dedicating the island of Murano for such facilities. Wagner’s search throughout metropolitan Detroit took similar concerns, such as the needs of the furnaces, into account. She also wanted an affordable space with access to good city services and shopping, proximity to her client base, and quiet. She found such a place in Pontiac, Michigan, which also had gorgeous views of the water and solitude. This idyllic location became home to epiphany studios in 1997.

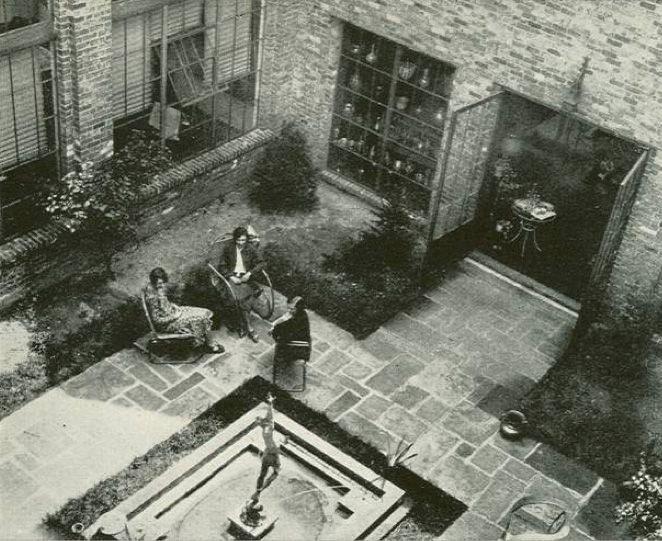

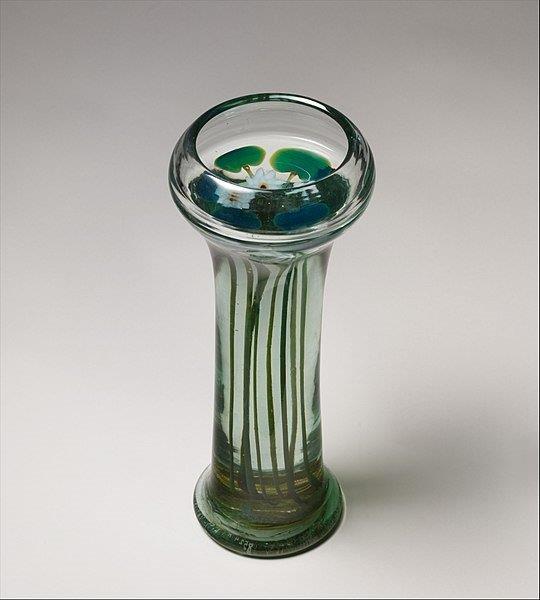

epiphany studios continues a long tradition among the glass studios and galleries in Michigan, dating from the mid-nineteenth century with the Detroit Stained Glass Works. Founded in 1861 by Charles Friederichs and Peter Staffin, studio designers, such as Ignace Schott, father of American painters Leon and Scott Dabo,11 produced ecclesiastical, domestic, and commercial windows for more than a century before closing in 1970. The Stroh Brewery Window, 1912, is representative of the firm’s more elaborate early twentieth-century work (Ill. 1). Art glass was retailed in Detroit at least by 1894, when L.B. King and Company open the firm’s new building on Library Street and Grand River Avenue in the city’s downtown. The six-story emporium specialized in imported and domestic glass and ceramics. Period advertisements and publications describe the firm as the leading establishment in Detroit for such material, including art pottery and glass pieces by Lenox, Rookwood, Mt. Washington Glass Works, and the New England Glass Company, such as the Wild Rose Lily Vase (Ill. 2).12 With the opening in 1916 of the Society of Arts and Crafts building on Watson Street, Detroiters were exposed to both the production and sale of art glass, art pottery, and metal work that embraced the idea of objects made by hand rather than machine. Designed by William Buck Stratton 13 and Maxwell Grylls,14 the building contained classrooms and studio space for work in a variety of materials, including glass and ceramics, complete with gas-fired furnaces and kilns. There was also a store that sold pieces made on premises, as well as those by leading Arts and Crafts artists from across the county (Ill. 3). In postwar Detroit, the Adler/Schnee store was legendary. Ruth Adler Schnee (an icon of the Detroit design world, along with her husband, Edward) opened a store in 1949 that introduced contemporary, mid-century design to Detroit, exposing the community to Danish modern furniture and the leading glassmakers from Scandinavia. It was located in the 1911 Hemmeter Building that towers over Harmonie Park, a small enclave that for the third quarter of the twentieth century and slightly beyond served as a center for galleries and design firms, such as the Detroit Artists Market, a venue that still represents the work of local artists, including glassmakers. More recently, Habatat Galleries opened in 1971 in Dearborn. Within ten years, art glass became the sole focus of the gallery, and Habatat, now in Royal Oak, has fostered a strong interest in contemporary glass and been a pivotal force in establishing the month of April as glass month in Michigan. epiphany studios is the latest addition to these premier studios and galleries. epiphany is Wagner’s production line, which is in keeping with the leading American art glass houses such as Quoizel, the various firms of Louis Comfort Tiffany,15 and Steuben.16

The epiphany line is designed with these objectives in mind: to create a wide variety of pieces using traditional and non-traditional techniques; to demonstrate excellent and expert craftsmanship; to employ an array of colors appropriate to both contemporary and traditional settings; to marry form and function, with each being of equal importance and value; and to be transparent in the design and production of the work. A significant aspect of epiphany studios production is its decanters and paperweights. Vessels and mesmerizing colored-glass objects have been a focal point of glassmaking since the days of the ancient Egyptians. Considered as precious and rare as gems, glass went beyond ornamentation to be cast and then blown into vessels. The earliest glass artifacts found in Egypt date to 1500 BC. The earliest documented glassmaking manual, dating to 650 BC, was found in the library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal. Roman glass production developed from Hellenistic Greek technical traditions from the third century BC. Initially, they concentrated on the production of intensely colored cast-glass vessels, although mosaic tiles and window glass were also produced. The technique of blowing glass developed in Babylon about AD 1. It quickly spread throughout the Roman Empire, along with such technological advances as the development of clear or aqua glass. Through the proliferation of glass blowing, the cost of glass declined by AD 100 and thus became available to the average citizens of the empire (Ill. 4).

As the Roman Empire fell into ruin, glass production and innovation also diminished until the second millennium, with the growth of the industry in the Republic of Venice. The colorful, elaborate, and skillfully made Venetian glass was the zenith of glass production well into the late nineteenth century. While other regions, such as the Czech Kingdom in the seventeenth century and England and the United States during the Industrial Revolution in the nineteenth century, became recognized for glassmaking, Venice maintained its leadership role in the field through craftsmanship, design, and innovation. These techniques were evident by the thirteenth century, when local artists developed the characteristic colors, transparency, and variety of decorative techniques associated with Venetian glass, including developing or refining crystalline glass, enameled glass, glass with threads of gold, multicolored glass, and milk glass (Ill. 5).

The earliest documented glass production began in the Czech Kingdom around the mid-thirteenth century. However, the major innovations that resulted in the region rivaling Venice occurred shortly after 1600, when Caspar Lehmann adapted the techniques of gem engraving with copper and bronze wheels to glass. At the same time, regional glass workers discovered that potash combined with chalk created a clear glass that was more stable than glass from Italy. Famous for its saturated color, Czech glass is even more renowned for its cut patterns. The technique involves adding one or more layers of glass to a vessel, then cutting patterns through the upper layers to reveal the clear glass below. In the second half of the nineteenth century, Bohemia embraced the export trade and mass produced colored glass, which tended to be inexpensive decorative objects, in factories. However, at this same moment, artists and designers in Prague became pioneers in the emerging art glass movement, exhibiting works at World’s Fairs in Europe and the United States. Although these early pieces of art glass may have been called “vase” or “compote,” they were never intended as utilitarian objects.17 The art glass movement continued through the twentieth century, including the communist era, when Czech glass sculptures were displayed in Expo 58 in Brussels and Expo 67 in Montreal (Ill. 6).

Wagner’s designs for the epiphany line continue the tradition of blown vessels that were first found in the homes of imperial Rome. Much like the great historic glass houses in Europe and the United States, with names like Gallé and Tiffany, the epiphany line consists of pieces designed and initially produced by Wagner. These are chiefly decorative objects balancing form, function, and beauty, and are produced either by Wagner or one of her studio artists. Each piece is hand engraved with the name epiphany. Some decanters, certainly a highlight of the line, recall work of earlier glass arts, while others address scientific issues. One such work is the Krackle Decanter (Ill. 7). Crackle glass was first developed in Venice during the sixteenth century. While in its molten state, glass was immersed in cold water, thereby cracking it. The glass was then reheated and either mold or hand blown, with the heat sealing the cracks. Interestingly, crackle glass is smooth to the touch on the interior, yet the exterior reveals the cracks. Some of the leading American nineteenth- and twentieth-century glass companies that were noted for using this technique were the Boston and Sandwich Glass Company; Mt. Washington Glass Company; Hobbs, Brockunier and Company; and the Blenko Glass Company. The sensuous, clean lines found in mid-century modern glass, produced by firms like Steuben, show a kinship with the Saturn Decanter (Ill. 8), which also recalls the fascination with space vehicles of the same period. It provides an interesting foil to the Crackle Decanter, from the same period, yet references different periods and techniques. Innovative in design, scientific achievement, and fabrication, the Tornado Decanter (Ill. 9) is truly the perfect balance of form, function, and beauty. The actual design lends itself to the function of decanting, aerating the wine as it enters and then exits the vessel. The functionality of this brilliantly designed piece enhances the beauty of the glass.

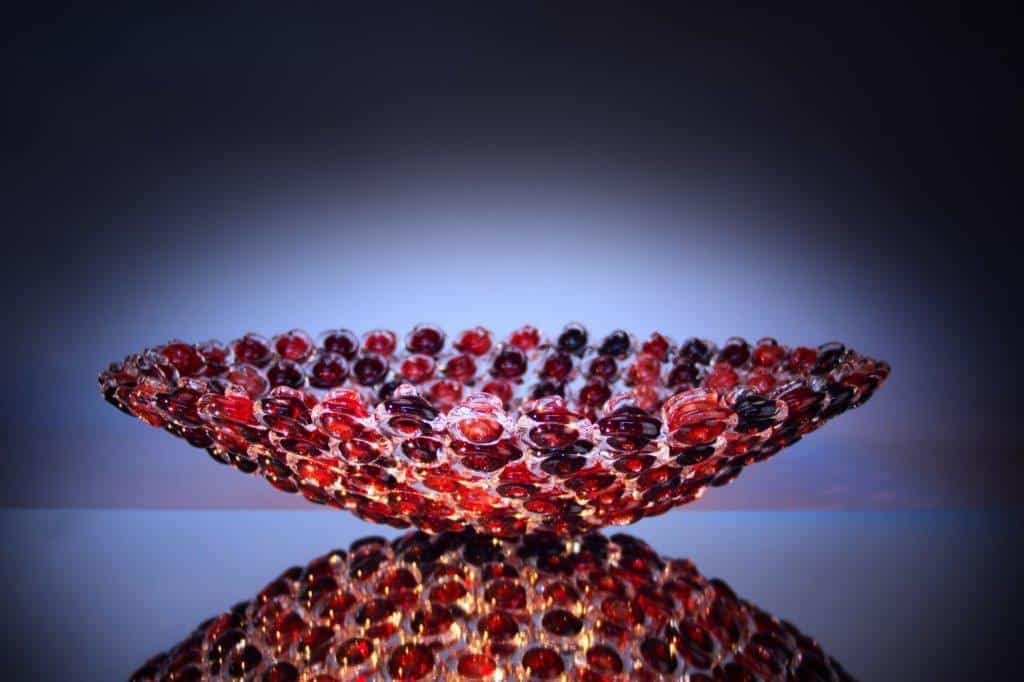

Two bowls, one belonging to the epiphany line and the other designed and fabricated by Wagner, recall work of earlier American glassmakers and offer insight into the difference between the production line and those works designed and fabricated by Wagner. Erupting from a clear glass base, the spring green basin of the Volcano Bowl (Ill. 10) flares outward, stretching toward the cobalt blue rim. This expressive explosion of glass recalls an important bowl in the collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), the monumental Lily Pad Bowl (Ill. 11). Lily pad bowls were a staple of American glass produced by New York and New Jersey glassmakers in the early nineteenth century. Fabricated with aquamarine glass, although occasionally in amber clear glass as well, these blown bowls with the overlaid lily pad came in varying sizes and would have been used in a broad range of households. That is not the case with the piece in the DIA collection, which is the most exuberant of any bowls produced of that form. Much like the Wagner piece, it begins on a low base and then dramatically flairs outward, cradled by the bold lily pad. The difference between the lily pad bowls offers some insight into the Red Peaz Bowl (Ill. 12).

Like the monumental Lily Pad Bowl, this was a standalone piece, differing from the production bowls that were undoubtably produced. It also reflects a mastery of skill that is seen in the Red Peaz Bowl, recalling the round three-dimensional elements found in windows designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany, like the Winter panel from the Four Seasons (Ill. 13). The three-dimensional elements assembled to form Wagner’s bowl are linked by what appears to be a glass skeletal system, not unlike the lead caming that holds together the three-dimensional elements that both frame the central design of the widow as well as form the pebbles cascading down its right side.

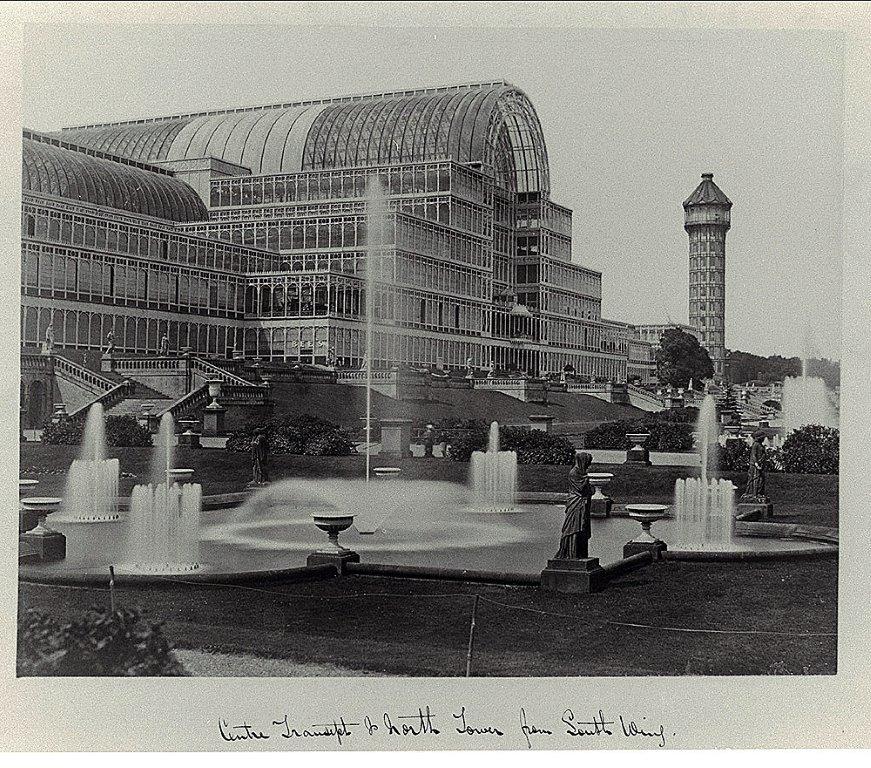

Paperweights first appeared in Europe during the second quarter of the nineteenth century. The Venetian glassmaker Pietro Bigaglia created and exhibited the first signed and dated weights at the Vienna Industrial Exposition in 1845. Many techniques employed by ancient glassmakers were re-created to achieve the illusionistic effects. These glass balls were considered such an artistic innovation that they were prominently exhibited at the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, housed at the Crystal Palace in London, sponsored by Prince Albert.18 Both the London and Vienna expositions played a significant role in creating the excitement and depth of interest these glass orbs held for nineteenth-century audiences and subsequent generations. While paperweights were widely produced, the French designs became the most sought after and exquisitely crafted (Ill. 14). Wagner has designed numerous paperweights of the epiphany line that reflect the techniques of those produced in France (Ill. 15), as well as that used by Louis Comfort Tiffany in his paperweight vases (Ills. 16).

The art glass movement began during the late nineteenth century, partly in response to the proliferation of machine-made products. Industrialization crept into many of the historic artisan traditions, like silverwork, metalsmithing, woodcarving/furniture making, and glass. The most prominent display of the industrialization of glass, which also served as a venue to introduce new artistic traditions, was the Crystal Palace, designed by John Paxton in 1851 for The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations (Ill. 17). It was the first monumental structure completely sheathed in a glass and cast-iron curtain wall. Blown plate-glass methods date to seventeenth-century London with continual refinements through the eighteenth century; however , it was the various industrial innovations during the first half of the nineteenth century that both lowered the cost and made construction possible, specifically, an automated system patented in 1848 that could produce a continuous ribbon of flat glass between rollers. The dimensions of those ribbons of glass dictated the size and shape of the cast-iron skeletal structural framework, a classic example of design following the dictates of production limitations.19 The vast number of identical panes required for construction drastically reduced both their cost and installation time.

While the nascent elements of the art glass movement were present at The Great Exhibition, the full-blown explosion of this work would not appear en masse for more than twenty years, when glass companies moved beyond decorative utilitarian pieces to purely decorative objects. The most elaborate of these pieces were often created to be displayed at great expositions in Europe and America from 1851 to 1939, if not to 1967. The role of these so-called World’s Fairs in driving awareness of progressive and avant-garde movements in furniture and the decorative arts, more so than painting and sculpture, cannot be underestimated. Visitors to the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia20would have been exposed to an array of glass forms produced by the New England Glass Company; Mt. Washington Glass Company ; and Hobbs, Brockunier and Company. Almost two decades later, at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, in Chicago, works by Louis Comfort Tiffany and the Libbey Glass Company would have been represented. These artists, and the firms for which they worked, along with later companies such as Steuben and Vineland Flint Glassworks, as well as their European counterparts such as Emile Gallé, Daum, René Lalique, Orrefors, Kosta Boda, and Loetz Witwe, to name a few, created and defined the art glass movement. This movement that initiated glass as art objects was not all production work; there were many individual commissions and singular works throughout the mid-twentieth century. Then, in 1962, a conscious effort was organized to bring glass into the reach of the artists working in their own studios. Although many of the designers and principals associated with the firms that produced art glass possessed the ability to fabricate glass and make singular works, the more common practice was to design a piece and leave the production to artists working at the actual furnaces.21 Harvey Littleton is considered the father of the American Studio Glass Movement and principal organizer of the glass-blowing seminar at the Toledo Museum of Art, which inaugurated the movement. He grew up in Corning, New York, where his father headed research and development for the Corning Glass Works. Littleton succeeded in changing the belief that glass blowing was relegated to the factory floor, apart from the designer at his desk; he placed the means of fabrication within reach of the individual artist.22 Artists that have furthered this movement are Dale Chihuly, Dan Dailey, and April Wagner.

Wagner began producing glass sculptures in 2000. These are works signed with her own name; they are not production pieces, nor do they tend to lend themselves to utilitarian purposes. Her nascent work included freestanding sculptural pieces, but eventually she moved to creating works that project or appear to be suspended as if airborne. She often creates unique, site-specific sculpture designed for various environments. These pieces vary from small studies or “sketches,” as she would call them, to monumental and complex installations. In her view:

“Glass has unique properties unlike any other material known to mankind. Glass is a material often taken for granted or overlooked in its everyday use but is truly Humankind’s Most Important Material and is the ideal medium for artistic expressions. Beyond its physical properties, it is tabula rasa, taking what the maker and the viewer bring to it.” 23

Much like that of Tiffany, Wagner’s work clearly draws inspiration from nature. Often, abstract elements begin to represent shapes and forms suggestive of blooms and blossoms, as in her early sculpture Lemon Iris (Ill. 18), which, at the same moment recalls the numerous floral pieces created by Georgia O’Keeffe in which the viewer is drawn into the very center of the blossom. Her sculptures can also be composed of representational elements, as in the whimsical Rabbit Lives at Claire’s House (Ill. 19). Wagner employs a variety of techniques in her work, thus, the glass elements that she fabricates to create her sculptures are of varied forms and textures. The gestural line she uses to suggest or create a form is reminiscent of Picasso’s figural line drawings from the mid-twentieth century, as is especially evident in Orange Petal (Ill. 20). Inevitably, the manner in which Wagner manipulates glass, playing with line and color to represent different types of flowers, vines, butterflies, and even mushrooms, brings to mind a glass garden, where light penetrates the crystalline foliage. There is another side to Wagner’s gardening, one that references the slightly surrealistic and bizarre work from popular culture, creating otherworldly plants like those in Little Shop of Flower (Ill. 21). Then there are assembled elements that call to mind a sense of rhyme, as in Seuss Flower (Ill. 22).

Ribbons, disks, and spheres in a symphony of color are manipulated into sculptural forms that appear to defy the laws of physics. The sense of movement is always present in these static structures, and yet questions arise as to how is it that these fragile creations do not collapse? What allows the assembled elements to remain in place? Much like a magician, Wagner does not reveal her secrets. In developing the pieces, she inquisitively investigates how simple, organic shapes look in space, questioning the quality of the line and exploring how the elements interact. In An Insolent Dragon (Ill. 23), the nature of the medium provides Wagner the opportunity to address concerns of orientation and the interplay of forms in space. As the light penetrates the piece, the color, opacity, and transparency change the visual weight within the sculpture, causing one’s eye to move across the multiple planes assembled.

Both bodies of Wagner’s work reflect the understanding of glass as a molten medium having inherent beauty.24 This idea is brought forth in her ribbon sculptures, which give a sense of motion to the static works, abundantly present with her Sahara Dancer (Ill. 24). As with many of the tabletop sculptures in which the elongated ribbons of glass recall pulled taffy, one wonders why the piece does not immediately sag and collapse. Thus, the molten quality of the medium is preserved in its hardened form. The delicately balanced elements within these sculptures also recall the early stabiles of Alexander Calder (Ill. 25). Prior to that kinetic artist’s invention of the mobile, his small tabletop pieces of delicately cut metal brought forth many of the questions Wagner thinks about in the creation of her pieces. And like Calder, Wagner is interested in bold, brilliant colors. Those saturated colors are clearly evident in many of her wall pieces. There the strong tones seem to bounce off the walls, yet due to their translucent nature the light pushing through the glass casts varying tonal hues on the wall (Ill. 26).

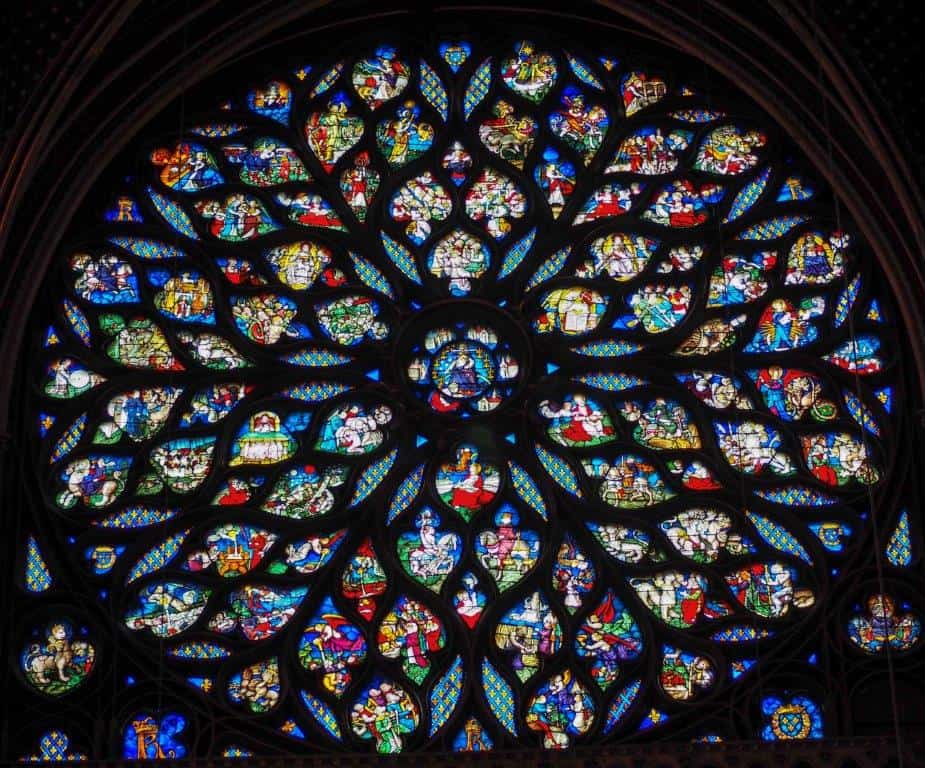

Wagner’s thoughts on the seductive beauty of glass echo the intention of the great stained-glass campaigns found in French Gothic cathedrals, where the light emanating through the colored glass against the walls of the structure tantalized and enticed the parishioners. “No matter what your definition of beauty is, glass draws the viewer to it like moth to a flame. Even when broken, marred, or flawed—like beach glass, for example—we as humans are compelled to investigate this sentient-seeming material.”25 In Wagner’s homage to the great Rose windows found high above the entrances to Gothic churches (Ill. 27), she has used glass ribbons to replace the stone tracery and left voids where the glass might have been (Ill. 28).

After well over two decades of seriously thinking about and working with this medium, Wagner’s interest has grown to glass moving in space. It is something that she has yet to experience. In a further shared kinship with Calder, Wagner expressed that she had long wanted to create a body of work that is kinetic in nature: “I am immensely intrigued by the idea of glass floating in space. This is when the material has a chance to really show off its beauty by bending, reflecting, and refracting the light in a way that makes it come alive.”26 Prior to this exhibition, she has not had the opportunity to explore those possibilities: “So as I learn and mature as an artist, I would say to date the entryway pieces and the large installation piece for this exhibit are my most significant to date.”27

Wagner’s passionate belief is that glass has permeated all aspects of our lives, changing the experience of being human in ways like no other material. It is not a far sentiment from the glass advertisement from the late twentieth century: when plastic had overtaken glass for bottling and storage, glass manufacturers chose to remind all that, “glass is best.” There is a question that artists and curators are inevitably asked for which there is truly no answer: “Do you have a favorite piece?” A better inquiry might be, “Is there a work that holds a special meaning or significance for you? When you think about your work or collection, what piece tends to come to mind?” For Wagner, the piece that she thinks of from an historical perspective is 3 Stars Up 1 (Ill. 29). For her,

“it is the quintessential example of the opposing forces inherent to glass. It perfectly speaks to the strength and fragility of glass; these carefully balanced parts seemingly floating in space, drawing the viewer in to see the graceful lines dancing around each other but also putting the viewer on guard, not to get too close for fear of tipping the piece off its delicate stance.”

For the rest of us, there is the experience of being submerged in a gallery with more than 80 objects that will visually stimulate and tantalize our senses. The blaze of color and sensuous forms that shimmer as the lights plays off the crystalline shapes will create impressions that turn into memories. Upon reflection, the recollection will be of sculptures and vessels, paperweights and gardens—with various pieces coming forth, holding a place that is representative of the entirety.

In the nineteenth century, milk of magnesia bottles were reused in west Africa and melted into cloudy blue beads.

Interview with April Wagner August 2018.

Interview with April Wagner August 2018.

Interview with April Wagner August 2018.

Interview with April Wagner August 2018.

The Center for Creative Studies, which began as the Art School of the Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts in 1926, (the Society was actually founded in 1906), change its name in 1975 and then again in 2001 to the College of Creative Studies.

Interview with April Wagner August 2018.

Interview with April Wagner August 2018.

Interview with April Wagner August 2018.

Interview with April Wagner August 2018.

Ignace Schott de Dabo shortened his name upon emigrating to the United States. His sons took their traditional French family surname.

Elbert Hubbard, A Little Journey to L. B. King & Company’s (East Aurora, NY: The Roycrofters, 1913).

William Buck Stratton was a Detroit-based architect extraordinarily influenced by English and American Arts & Crafts movement, as demonstrated by his numerous structures in the greater Detroit area. He was also the husband of Mary Chase Stratton, founder of Pewabic Pottery.

Maxwell Grylls was one of the principals of the Detroit-based firm Smith, Hinchman and Grylls, now the SmithGroup. It is the oldest contiguous architectural firm in the country.

Louis Comfort Tiffany was the son of Charles L. Tiffany, the founder of the New York silver manufacturer and jeweler Tiffany & Company. While there were some collaborations with his father’s firm and the designers that worked there, the two were distinct and separate entities.

Steuben was especially established as the art glass line for the Corning Glass Company, which also has a scientific line Pyrex. To this day, no chemistry lab is without their product or their forms.

Monumental examples of Czech glass in Michigan include the chandeliers designed and fabricated by the pioneer in American architectural lighting, the Edward F. Caldwell and Company, hanging in the three-story lobby of the Fisher Building on Second Avenue and Grand Boulevard in Detroit, and the yellow luminous glass panels in the ceiling of the main banking room of the Guardian Building on Griswold Avenue in Detroit, designed by Augustus D. Curtis, pioneer of indirect lighting.

The Corning Museum of Glass, research website, paperweights.

These were the largest glass panes available at the time, produced by Chance Brothers of Smethwick, and measured 10 inches wide by 49 inches long.

The International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures, and Products of the Soil and Mine was the official name of the Centennial Exposition. The first official World’s Fair in the United States, it was held in Philadelphia from May 10 to November 10, 1876, ostensibly in celebration of the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The exposition was in Fairmount Park along the Schuylkill River on grounds designed by Herman J. Schwarzmann. Thirty-seven countries participated in the exposition, which had an attendance of 10 million people.

A noted late nineteenth- to early twentieth-century example was between the two leading American stained-glass artists, John LaFarge and Louis Comfort Tiffany. LaFarge actually produced, with his assistants, all the glass for his commissions, whereas Tiffany had the glass for his projects either produced at one of his facilities or purchased the material. The Tiffany model was far more lucrative, and LaFarge faced numerous financial setbacks throughout his career.

Dan Klein, Artists in Glass: Late Twentieth Century Masters in Glass (London: Mitchell Beasley, 2001).

Interview with April Wagner September 2, 2018.

Interview with April Wagner, September 10, 2018.

Interview with April Wagner, September 10, 2018.

Interview with April Wagner, September 10, 2018.

Interview with April Wagner, September 10, 2018.

Thanks for reading! As always, you can stay up to date with us on Instagram, Facebook and sign up for our weekly newsletter.